Machine Gods

On crises of faith, slop, and the art of medicine

Any doctor who can be replaced by a computer deserves to be replaced by a computer.

— Warner Slack

One of my favourite podcast series is The New Gurus, by Helen Lewis, produced in 2022. Here, she highlights one of the world's most significant cultural shifts: people’s burgeoning obsession with gurus, influencers, and quasi-religious movements. You can see it in the rise of influencers like Andrew Tate, the zealous embrace of niche wellness and productivity practices, and the steady drumbeat of new conspiracy theories. Not to mention, crypto. Helen traces this shift to a lack of faith in institutions and a newfound scepticism of experts. However, on closer listening, it’s clear that Helen Lewis is lamenting something else. Our collective, societal loss of God.

This is a modern twist on an old problem. In 1883, Nietzsche wrote, “God is dead”, in an attempt to warn us that we would have to divine new meaning in life after belief in rationality and science killed our belief in God. For millennia, religion acted as an organising principle, a set of moral precepts, and a social movement. Religion offered a simple promise: live well, be a good neighbour, and receive salvation. Nietzsche believed that society would have to wrestle with the belief system that emerged in the wake of God’s death, and he was right.

Nietzsche wasn’t the only one who cautioned us about this. In his infamous commencement address, David Foster Wallace highlights that we all worship, whether we like to believe it or not. So instead, he challenges us to ensure we are worshipping the right thing.

Because here’s something else that’s weird but true: in the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And the compelling reason for maybe choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship–be it JC or Allah, be it YHWH or the Wiccan Mother Goddess, or the Four Noble Truths, or some inviolable set of ethical principles–is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive.

— David Foster Wallace, This is Water

There is a reason why the second step in Alcoholics Anonymous is subjugating oneself to a higher power. This is because only when you reorient your eyes upwards and your belief system outwards can you begin to fully adjudicate the decisions you made. When what you worship is alcohol, you'd best be sure to have a new god to replace it.

The subtext is clear. Humans need something to believe. We worship on the altar of a satisfying, unifying narrative. It is terrifying to imagine that things just are, with no cause and effect, that we are, in fact, just buffeted along by the winds of fate. Our first reflex, when we hear of a freak accident involving someone who seems, on the surface, undeserving, is to dig just that little bit deeper to find out why they might be. And through our questions, pressure the narrator to reveal why it could never happen to us. That there was a reason why it happened to them and why we, rational, kale-eating, intelligent, non-drinking drivers, are safe from the random and rapacious vicissitudes of life.

So there it is. The challenge. What do we believe when belief is gone? What do we worship when we have lost trust? Who becomes God, when God is dead?

Artificial intelligence

In his 2017 book, The Four, Scott Galloway reminds us that we might not need to look up to heaven for God, but instead down to our keyboards. His view was that for much of the Western world, we have a new digital God, Google.

One sense in which Google is our modern god is that it knows our deepest secrets. It’s clairvoyant, keeping a tally of our thoughts and intentions. With our queries, we confess things to Google that we wouldn’t share with our priest, rabbi, mother, best friend, or doctor. Whether it’s stalking an old girlfriend, figuring out what caused your rash, or looking up if you have an unhealthy fetish or are just really into feet—we confide in Google at a level and frequency that would scare off any friend, no matter how understanding.

— Scott Galloway, The Four

The parallel is obvious. Google divines us answers. It solves our problems. And it’s on 24/7. You could argue that it is omniscient (all-knowing), omnipotent (all-powerful), and omnipresent (everywhere, all at once). God-like technology, accessible at our fingertips. For free.

But Google, for all its godlike qualities, remained responsive rather than proactive. We confessed to it; it did not anticipate our sins. We asked; it did not offer. The boundary between human agency and machine assistance remained clear.

Then, in November 2022, ChatGPT arrived. However, this time, the gods gave us an upgrade. Not just omniscient but conversational. Not just answering queries but remembering your preferences. Not just listening passively, reaching out proactively. Becoming a friend. A confidant. A lover. Someone you can ask about your dreams. Most insidiously, it can do the work of thinking for you. Draft the essay, reply to the email, create the strategy, build the website, etc. You think it, and in most cases, ChatGPT or similar can do it.

This convenience comes at a cost. When we outsource not just toil but labour itself—not just the burdensome email but the essay, not just the form-filling but the thinking—we risk what Will Manidis and others call “slop”: creating without the act of creation. Production detached from genuine human contribution. The devil’s oldest bargain: godlike results without godlike effort.

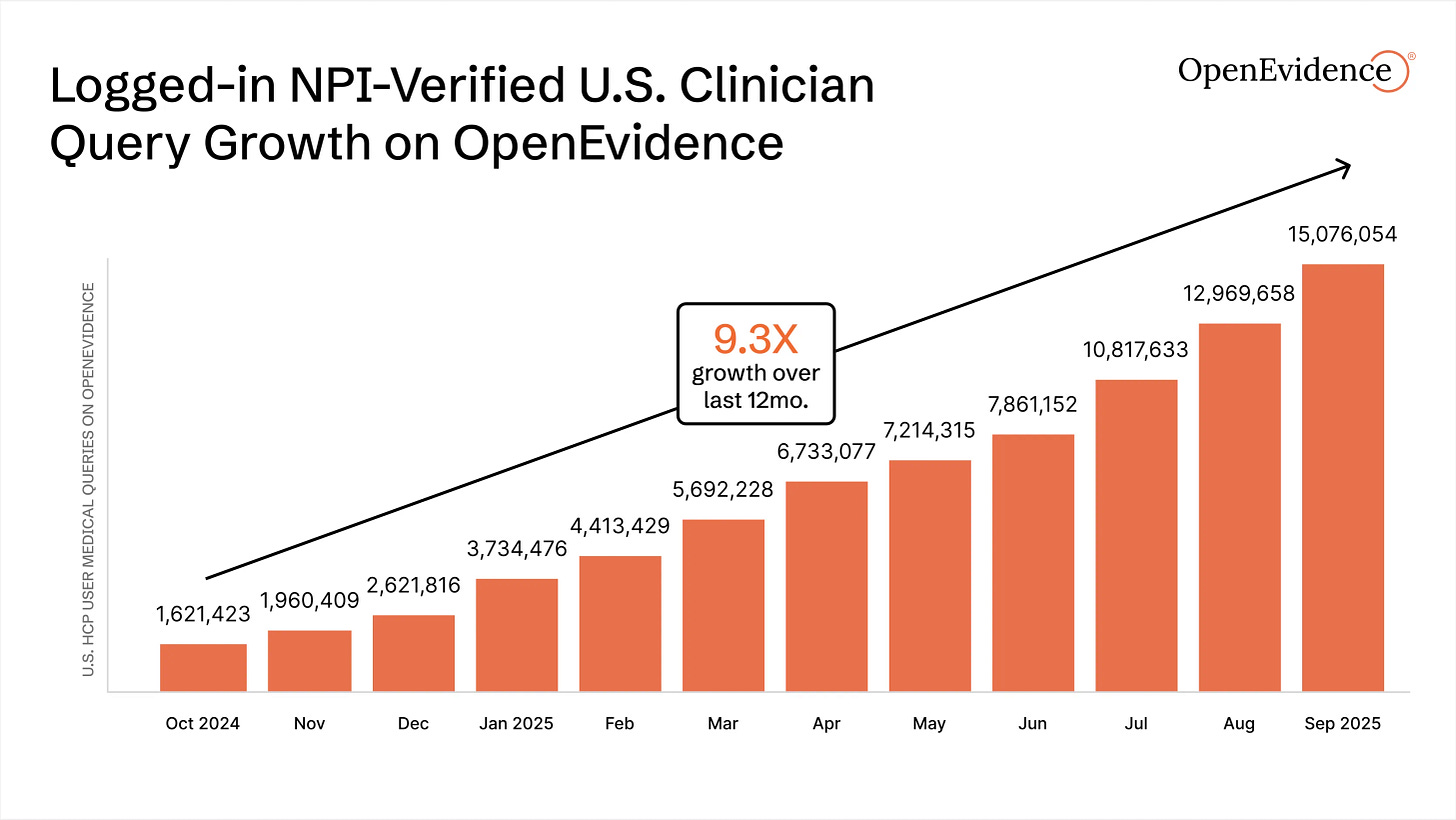

Medicine is not immune to this temptation. Companies using large language models, such as OpenEvidence, Doximity, UpToDate, and Glass Health, are helping doctors answer clinical questions, provide diagnoses, recommend treatments, and more. Doctors are flocking to these tools en masse. On OpenEvidence alone, clinicians performed 15 million queries this September. A nine-fold increase from last year.

This was coming. Studies have shown that large language models (LLMs), without specific training on medical texts, are effective diagnosticians, adhere to clinical guidelines, and produce high-quality management plans. And when LLMs on their own are pitted against humans or humans augmented with LLMs, LLMs on their own always win.

A typical review of these tools goes something like this, from Coatue’s OpenEvidence investment memo:

“I don’t know of any other tools that do what OpenEvidence does. The ability to query and get immediate results that are dynamic and relevant is unique. No one can keep up to date on all areas of medicine, so this is the best way to stay up to date on what the leading journals recommend.”

It sounds like clinicians may have found their God! And look at how much toil it’s replacing! Over 3 million scientific, technical, and medical (STM) articles were published in 2018. This has only risen since. No one could possibly keep up. These tools are reducing the burden of knowledge, freeing up clinician capacity, and democratising medical information once stuck in silos. If my family member went to the ER, I’d want the attending to have access to an indefatigable entity that has absorbed all the content of the internet, all medical textbooks, and read last week’s paper about a new treatment for her condition.

How should doctors adapt to such powerful tools? I’ve heard about two distinct approaches. The first is cautious: take the history, order the scans, send the bloods, then use AI to check for gaps. The second is wholesale outsourcing: dump the patient’s context into the algorithm and ask what it thinks. History by vibes. Medicine as prompt engineering. No labour. No craft. Call this the sloppification of medicine.

There is precedent for this second approach in chess. In 2017, twenty years after Deep Blue (a chess supercomputer) beat Garry Kasparov (the then chess world champion) in a seminal set of matches, he wrote a book called Deep Thinking. Here, he extolled the idea that in the next iteration, it wouldn’t be the best machine beating the best human; humans and machines would always beat machines on their own. His idea was one of augmentation; that human creativity combined with machine calculation would consistently achieve superior outcomes compared to either alone. It wasn’t long before he was proved wrong.

Post AlphaZero (a program launched in 2017, months after Garry’s book had hit the shelves), chess machines are untouchable at chess, either by humans or by humans working in collaboration with machines. In fact, in these scenarios, humans worsen the machine’s decision-making.

So the thinking goes, AI is inevitable. Let it cook. Why labour with the limitations of the human mind when we can get the Answer?

I think there’s a better way. A way in the middle. Not abdicating thinking, but also not ignoring the incredible benefits of these new tools.

So, what should doctors do?

Doctors must focus on the sacred. They must exercise dominion over what I believe is the new craft of being a doctor. Obsessing over the patient, absorbing the totality of their humanity — their needs, finances, relationships, preferences — and doing the hard work of truly listening, not just waiting for them to stop speaking.

Remember that a diagnosis delivered without understanding what it means for this patient’s life is just pattern recognition. A treatment plan that doesn’t account for the person who can’t take time off work, or the elderly patient who’d rather have six good months than twelve diminished ones, is the realm of the faceless algorithm. The doctor’s role is not to compete with AI on its own terms, but to play an entirely different game, where the rules are negotiated with each patient and where winning means something different every time.

Consider the 68-year-old with newly diagnosed colon cancer. The algorithm calculates survival probabilities: surgery plus chemotherapy offers 60% five-year survival; surgery alone, 45%. Clean numbers. But the algorithm doesn’t know that her husband died six months ago, that her daughter lives in Australia, that she’s terrified of becoming dependent on her estranged son. The doctor who asks, ‘What matters most to you now?’ and actually listens to the answer: that’s the craft AI cannot replicate. Not because it’s mystical, but because it requires synthesis of a different order: medical knowledge and this particular life, in this particular moment.

Some will argue this is professional vanity dressed as humanistic care. If AI improves diagnostic accuracy, guideline adherence, and outcomes, isn’t resistance just ego? But this misunderstands what outcomes we’re optimising for. Medicine is not simply achieving the statistically optimal result. It’s achieving the right result for this patient, given their values, their context, their life. AI can optimise for five-year survival. Only humans can ask whether those five years are worth what they’ll cost this particular person.

This is not a call to romanticise inefficiency or resist tools that genuinely reduce suffering. Let AI handle the prior authorisations, generate the discharge summaries, and translate the key documents. Let it support diagnosis and management. But recognise that clinical expertise is not just knowing, it’s judging. Knowing when to deviate from guidelines. Judging which outcome matters most to this particular person. Holding space for uncertainty when the algorithm demands certainty.

Warner Slack was right that doctors who can be replaced by computers deserve to be replaced. The task ahead is ensuring we cannot be, not through gatekeeping or pride, but by becoming irreplaceable at the things that matter most: the conversation that reveals what the patient actually fears, the gentle correction that shifts a family’s understanding, the willingness to say ‘I don’t know, but I’ll stay with you while we find out.’

The question is not whether AI will replace doctors, but whether doctors will let themselves be reduced to what AI can do.